By Raya Tahan

The Arizona Daily Star

Extending her light brown leathery neck and two-foot-long flippers, Adelita paddles due west at about 100 miles each week.

The 223-pound loggerhead turtle is half way along her 6,000-mile-plus trip from Baja California to her birthplace of Kyushu Island, Japan.

Scientists and schoolchildren across the country are following Adelita's trek with the help of a radio transmitter that's bonded to her shell.

When she surfaces for air, the one-pound transmitter beams her location to a satellite. The satellite downloads her whereabouts to a private company, which e-mails two University of Arizona marine biologists.

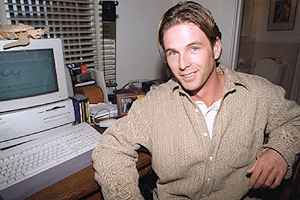

One of them, Wallace J. Nichols, then updates the Internet home page dedicated to Adelita's journey. He also describes her trek on the home page of the Coastal Conservation Foundation, a non-profit organization that he and colleague Jeffrey Seminoff founded in 1993 to help preserve marine life in the Gulf of California.

``A lot of people have been really touched by this turtle swimming across the ocean,'' Nichols said. ``It's exciting to be able to offer more than new data to the scientific community.''

Adelita began swimming Aug. 10 just off the coast of Santa Rosalillita, a town midway down the peninsula. Now she's about 300 miles northwest of Honolulu.

She was released by Nichols, Seminoff and Antonio Resendiz, a marine biologist with Mexico's Centro Regional de Investigacion Pesqueara.

``That was the time that we knew the seas would be calm,'' Seminoff said. ``It's like glass during that period of time.''

Since then, he has received dozens of letters and e-mail messages from teachers who incorporate the data with lessons in geography, biology and even cultural studies.

A middle school English teacher from California sent him a poem that her class composed about Adelita.

``Using the migration of one animal, we really bridge into many other fields of science,'' Seminoff said. ``Through following the sea turtle and having the information available on the Internet, kids can really expand their horizons and have their fingers on the pulse of real science.''

But schoolchildren aren't the only ones learning from Adelita's journey.

Scientists believe that loggerheads instinctively migrate from Japan's shores to Baja California as hatchlings who weigh several ounces.

They live in the coastal waters off the peninsula, feeding on the abundant red crabs and lobsters, Seminoff said.

Anywhere from 10 to 30 years later, the loggerheads return to Japan to mate, he said.

But many questions about this ritual remain unanswered, Nichols said.

``It may be that there's a corridor, like a band of water, that has necessary oceanographic conditions,'' Nichols said. ``It might include currents and a source of food like jellyfish. . . . Maybe there should be some special protection in that area.''

But that information is ``just the tip of the iceberg'' as far as what the researchers want to learn, Nichols said.

After tracking more turtles, they hope to conclude whether loggerheads make only one round-trip in a lifetime or whether they continually circulate. They also hope to learn whether sea turtles travel alone or in groups and whether males follow the same migration patterns as females, he said.

Adelita had been raised in captivity since 1986. She weighed about eight pounds when a fisherman accidentally netted the young turtle and brought her to Resendiz. He spent eight years studying her growth, feeding habits and breathing rates.

When Resendiz met Nichols and Seminoff in 1993, the three formed a partnership. They extended studies of Adelita to include her migration habits.

Each of the world's seven species of sea turtles migrate from their birthplace, then return home to mate. But none are thought to travel as far as the loggerhead, Nichols said.

Every species is listed as threatened or endangered. Many become victims of poachers or beachside developments. Others get caught as fishermen sweep nets across the ocean floor, Nichols said.

He hopes the attention generated by Adelita will help alleviate the sea turtles' declining population.

``Adelita sort of personalizes the whole set of issues,'' he said. ``She gives sea turtles a name. She opens up some discussion and gives people a starting point to think about marine conservation in general.''

On July 19, 1994, Nichols and Seminoff labeled a loggerhead turtle with a number tag. She was found dead 16 months later in a Japanese fisherman's net, proving that loggerheads do, indeed, cross the Pacific Ocean.

On Jan. 13, they bonded a satellite tag to a black turtle they believe migrated to Baja California from Southern Mexico.

Four elementary and middle schools - two near Cincinnati and two near San Diego - are raising funds to sponsor transmitters for sea turtles in the future. The transmitter and data acquisition service cost $5,000 per turtle.

Nichols and Seminoff have raised funds to pay for half of four more transmitters.

``If there's a local school who wants to sponsor a tag but can't afford the whole weight, we've got several tags that are half sponsored,'' Nichols said.

Teachers who want to include Adalita's trek in their lesson plan can e-mail Nichols at jnichols@ag.arizona.edu.