"I thought, can there really be so many of these beautiful animals that they could be harvesting so many for turtle steak?"

-- G. Balazs

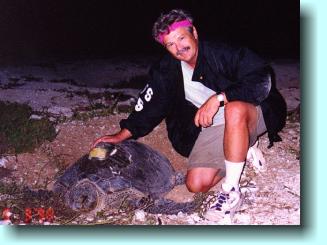

Photo by Ursula Keuper-Bennett

(45K JPEG)

The following article appeared in the Sunday, July 19, 1998 edition of The Maui News. Reproduced here with permission.

Twenty five years ago, at a time when you could walk into popular Maui restaurants and find "fresh caught" turtle steak on the menu, a marine biologist named George Balazs kissed his wife good-bye and went to live among Hawaii's green sea turtles.

He boarded a DC-3 "Gooney Bird" aircraft of World War II vintage, and departed his home in Honolulu. His destination was 500 miles away, a cluster of tiny islands known as French Frigate Shoals. Located halfway between Midway Island and the Big Island, they are today part of the Hawaii National Wildlife Refuge.

Balazs wanted to learn more about Honu, the Hawaiian green sea turtle, in the area where it nested. "I began to wonder about the numbers of green sea turtles in Hawaii back in 1969, while sitting with my wife by the boat ramp in Lahaina Harbor," says Balazs. "We saw boats arriving that were loaded with stacks of live, green sea turtles, which were carted up to the tourist restaurants."

"I thought, can there really be so many of these beautiful animals that they could be harvesting so many for turtle steak?"

"I thought, can there really be so many of these beautiful animals that they could be harvesting so many for turtle steak?" -- G. Balazs Photo by Ursula Keuper-Bennett (45K JPEG) |

|

He knew from historical accounts that from mid-May through August the French Frigate Shoals were a nesting area for the green sea turtles found around Maui and the other Hawaiian Islands. But, according to Balazs, there was much more to be learned.

"Not much was known then about such things as how many green turtles nested in Hawaii, what nesting cycles they displayed, the turtles' dispersal throughout Hawaii, the growth rates of youngsters, and the time to maturity," says Balazs, who today is the leader of the Marine Turtle Research Program at the National Marine Fisheries Service laboratory in Honolulu.

"What was clearly known at that time in Honolulu and on Maui, was that a good market and high price existed in the restaurant trade for green turtle meat."

According to Balazs, the turtles had no legal protection at that time (it was five years before green sea turtles were protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act), and anyone with a net, spear, gun or grappling hook could easily catch turtles.

Twenty-five years later, the anniversary of the start of his study is being lauded by friends, volunteers, co-workers, conservationists and scientists who consider Balazs to be the world's authority on the Hawaiian green sea turtle.

| "He's also the honu's most dedicated and effective advocate." -- U. Keuper-Bennett Photo courtesy G. Balazs (62K JPEG) |

"No one knows more about the Hawaiian green sea turtle than George Balazs. He's also the honu's most dedicated and effective advocate," said Ursula Keuper-Bennett, a Canada resident who comes to Maui each summer with her husband Peter to dive with the sea turtles at Honokowai. The Keuper-Bennetts have created a tribute to Balazs on the Internet, as part of "Turtle Trax", their web site devoted to their own findings about sea turtles.

"Whenever anyone says 'turtles' in Hawaii, you think of George Balazs," says Eric Brown, senior researcher with Pacific Whale Foundation's Coral Reef Research Project. "He is at the pinnacle of turtle knowledge here."

However, Balazs' study did not begin with a blaze of glory. On his first night at French Frigate Shoals, he stayed on Tern Island, a 26-acre atoll barely large enough to accommodate a 3,000-foot gravel runway. When evening arrived, Balazs searched for turtles -- with disappointing results. "No signs of nesting turtles observed," he wrote in his field note book for June 1, 1973.

Two days later, he packed his gear into a 16-foot boat and traveled to East Island, six miles away. As he anchored close to shore, a 10 -12 foot long tiger shark bumped the propeller on the boat's outboard motor. "I wondered, how am I ever going to take a bath?," laughs Balazs.

As the sun dipped toward the horizon, he began searching for nesting turtles on the 12-acre island. The screeching of the tens of thousands of sooty terns that literally covered the island was deafening. But again, no turtles.

Fortunately, as darkness blanketed the island, Balazs encountered his first nesting female. She dragged her 250-pound body onto land, using front flippers better suited for swimming than walking. Laboring hard, she pulled herself high above the tide line, the terns screaming and pecking at her as she crawled over their eggs.

Sand flew as she began to excavate a nest, creating first a cavity in the shape of her body. Intently, paying no notice to Balazs, she then used her rear flippers to carve a bottle-shaped hole in the sand. Straddling the hole, she laid about a hundred leathery golf-ball sized eggs, which she covered with great care before pulling herself back to the sea.

During that first season, Balazs counted just 67 nesting females. He tagged each one with a small metal tag, to avoid counting them more than once, then recorded each turtle's measurements.

| He tagged each one with a small metal tag, to avoid counting them more than once, then recorded each turtle's measurements. Photo courtesy G. Balazs (75K JPEG) |

So that he could study the turtles at night, he slept by day, his small tent oven-like under the intense mid-day sun. At night, he groped around in pitch blackness, avoiding switching on his flashlight because it would attract piles of tiny hatchlings against his tent wall. (Hatchlings are born with an innate attraction to light, which helps them locate the ocean at night.) Although happy to be around the turtles, he missed his family and was dismayed by the extreme loneliness and isolation. In his field journal, he described his setting as "paradise and prison all in one."

From those humble beginnings grew an impressive study of Hawaii's green sea turtles. Every year over a quarter century, Balazs and his team of researchers have systematically counted nesting turtles on East Island, creating an index that gives Balazs and other biologists a sense of the turtles' population levels.

"That first year, we found 67 nesting turtles,'" said Balazs. About 100 turtles were counted in 1978, the year in which the U.S. Endangered Species Act made it illegal to hunt, kill or harass sea turtles. In the years that followed, the numbers of nesting turtles began to increase. Balazs' team counted about 150 in 1981, then nearly 300 in 1989. The numbers went up to 384 in 1993. Last year was the best year on record, with 504 nesting females counted.

"What I'm seeing now, compared with what I saw in 1973 on those first nights on East Island, is very gratifying, very satisfying," reflects Balazs. He points out that although the signs are encouraging, the numbers are well below historical levels.

"Vessels that came to French Frigate Shoals in the 1800s reported that there were hundreds of turtles basking on the islands, resting side by side," he said.

In addition to counting nesting turtles, Balazs has sought to learn about the migratory paths of the turtles. He has tagged 2,000 nesting turtles, first with metal tags, and most recently with PIT tags (the internal tags used by veterinarians to identify cats and dogs) which last longer in the marine environment. His team has also tagged 3900 other turtles, mostly juveniles and subadults in their feeding areas. He was also the first person to successfully use satellite tagging to track the migratory paths of mature sea turtles departing their nesting beaches.

"We now know that 90% of all the turtles found in Hawaii are born at French Frigate Shoals," says Balazs.

"We now know that 90% of all the turtles found in Hawaii are born at French Frigate Shoals." -- G. Balazs Photo courtesy G. Balazs (58K JPEG) |

|

The adults return to their natal beach, the beach on which they were born, to nest.

According to Balazs, it takes about 25 years for a turtle to reach adulthood. Adult females migrate to breed once every two or more years, while the adult males often migrate on an annual basis. (The turtles mate offshore, then the females come ashore to nest.)

Balazs is also working to understand sea turtles throughout their life cycle. This is difficult because once the hatchlings enter the sea, they drift in the ocean currents, feeding on fish eggs and invertebrates. It is only when they have grown to about 8 - 10" long that they appear near shore, where they settle in at "feeding pastures" to feast on their adult diet of seaweed, sea grass and limu.

Last week, Balazs was at Palaau, on the south shore of Molokai, working on a cooperative tagging and monitoring project with Hawaii's Department of Land and Natural Resources and Department of Aquatic Resources. The project, established in 1981, has tagged and measured a total of 1,458 turtles. Each year, the project team has been able to recapture 10 - 35% of the previously tagged turtles. By measuring turtles each time they're recaptured, Balazs has been able to learn the rate at which turtles grow (7/8 inch per year in carapace, or shell, length).

This long-term study has also documented at the site an outbreak and build up of a tumor-forming disease known as fibropapilloma. Sadly, 50% to 60% of the turtles at Palaau have exhibited these deadly tumors in recent years, which can cover the soft tissue of the turtles, blinding the animals and leaving them unable to feed. The disease is not found along the Kona coast, but is prevalent among turtles in areas of Maui and Molokai. For example, during 1989 and 1990, tumors were present in 77% and 85% of the turtles stranded on the island of Maui, mainly in the Kahului Bay area.

A vigorous research effort is underway to determine the cause and cure for the disease. Researchers have found that the disease is caused by a retrovirus and herpes virus, says Balazs.

Yet, in spite of the disease, Balazs is encouraged by the positive signs for the Hawaiian green sea turtle population. "The increasing numbers of nesting turtles at French Frigate Shoals are an example of what can happen when the state, federal government and community work together to protect a species," he says.

He notes that sea turtles have moved from being a menu item to a popular tourist attraction. Numerous snorkel cruise brochures on Maui promise visits to "Turtle Town" (a reef located near the Maui Prince). When docked at Kahului Harbor, American Hawaii Cruises takes its passengers on a turtle walk, to view the 30 or more green sea turtles that bask each evening in the warm water discharge from the Maui Electric Company power plant.

At the same time, the field work continues at French Frigate Shoals. "East Island has a sameness, year after year," says Balazs. "When I'm there, it could be 1973 again."

| "When I'm there, it could be 1973 again." -- G. Balazs Photo courtesy G. Balazs (62K JPEG) |

French Frigate Shoals--25th Anniversary

French Frigate Shoals--25th Anniversary